As a high school student, Cadet Jacob Benny ’22 had a natural talent for math, and he also discovered an interest in physics.

But work on a project for NASA before he’d even earned a college degree? That seemed to be an out-of-this-world ambition.

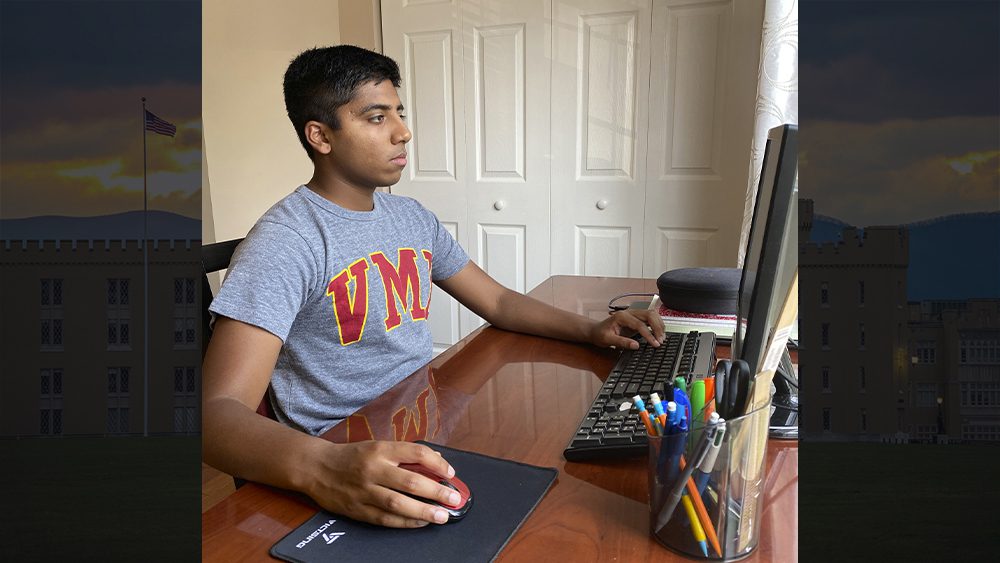

This summer, the mechanical engineering major described himself as “a kid in the candy store” as he worked on a project for NASA Langley’s Vertical Solar Array Technology Group in support of the Artemis project, which seeks to return humans to the moon by 2024. Benny’s work, which is being funded by NASA Langley, may someday be used to help power lunar rovers and other devices on the moon.

NASA probes have found evidence of water at both the north and south poles of the moon, explained Col. Joseph Blandino, Ph.D., professor of mechanical engineering, who is overseeing Benny’s work. That bodes well for human settlement and survival there—as does the fact that much of the water is located at the south pole of the moon, which gets almost constant sunlight. Because of this, it’s possible to charge batteries by means of a deployable photovoltaic solar array.

But it’s never that easy—especially away from planet Earth. Benny described the moon as “a harsh thermal environment” in which one side of a solar array is always going to be hot and the other is always going to be cold. “There will be some kind of thermal bending,” Benny observed.

To prevent this issue, which could lead to problems deploying and retracting the solar array, Benny sought to make two computer programs, Thermal Desktop and Abaqus Finite Element Analysis, talk to each other.

As he did so, he built on the work of Jerry Haste Jr. ’21, whose Institute Honors thesis, “Temperature Profile of a Photovoltaic Array Located at the South Pole of the Moon,” was one of five recipients of the Wilbur S. Hinman Jr. ’26 Research Awards at this year’s Institute Awards ceremony.

“[Benny] is looking at the thermal issues and developing a code where [Haste] started that performs a coupled thermal structural analysis,” Blandino explained.

For Benny, the hardest part was learning two software packages—Thermal Desktop and Abaqus—at the same time, plus two computer programming languages, C# and Python.

“The most difficult part of the project has been getting introduced to all of these programs,” he commented in July. “It’s a lot to handle, but I’m really enjoying it. There’s a lot of layers of the onion. You keep peeling, and you go, ‘Oh, I need to learn something about this tool.’”

He’s also enjoyed his mechanical engineering coursework at VMI. “Mechanical engineering is super, super fun and interesting to me,” said Benny, who plans to commission into the Navy after VMI. “I have a blast in class.”

His work may just help others blast off from the Earth’s surface. Exploring the outer solar system has been a dream for humankind for centuries, yet despite all of our technological advances, no one has been there yet.

To boldly go where no man has gone before, it’s best to start from the moon. Not only does Earth’s only satellite have one-sixth of our planet’s gravity, but since the moon has water, and water is made up of hydrogen and oxygen atoms, it’s possible to split water molecules apart into their component parts and make rocket fuel.

“If you can produce your fuel on the moon, you’re cutting your costs roughly by half to explore the outer solar system,” said Blandino. “What [Benny] is doing is an important part of this.”

As for Benny? To say that he’s amazed at the direction his cadetship has taken would be an understatement.

“I wouldn’t have rated myself as a really good candidate coming out of high school, transcript-wise and everything,” he commented. “I’ve taken the opportunities at VMI and just run with them—worked as hard as I could.”