“It’s kind of like a fight—an exchange—with the patent office, because they’re trying to either refuse the patent application or else have it restricted as much as possible,” Portavoce said, describing the patent application process. “Whereas for the client, you’re trying to get as much protection as possible, so you’re trying to keep it as broad as possible. … It’s kind of this push and pull with the office, and it can last five years or more.”

Often, Portavoce works with ideas that are not yet tangible products or are invisible to the naked eye. “When it’s an actual product, it’s fun to see.”

She remembers one client, who specialized in noise reduction and sold things like noise-reducing headphones. This time, the client wanted to make a quieter hairdryer. Normally, hairdryers take in air at the back and send out the hot air in the front. The client had several ideas about different air intakes that could reduce the noise, including at the bottom of the handle and through a spiral configuration. In the exchanges with the patent office, the examiner “kept coming up with these previous patents from 20, 30, 40 years ago that had similar ideas.” A large, well-known company also filed objections to the grant of the patent. The patent attorneys asked the client to focus on the design that best matched the product they planned to produce. The client followed the advice. A quieter hairdryer, with a design that takes in air from an inlet surrounding the outlet in the front, is now patented and on the market.

Working in patent firms is intensive, demanding, and requires long hours. In Europe, one must work as an apprentice under a licensed patent attorney for a minimum of three years before being able to even sit the exams, Portavoce explained.

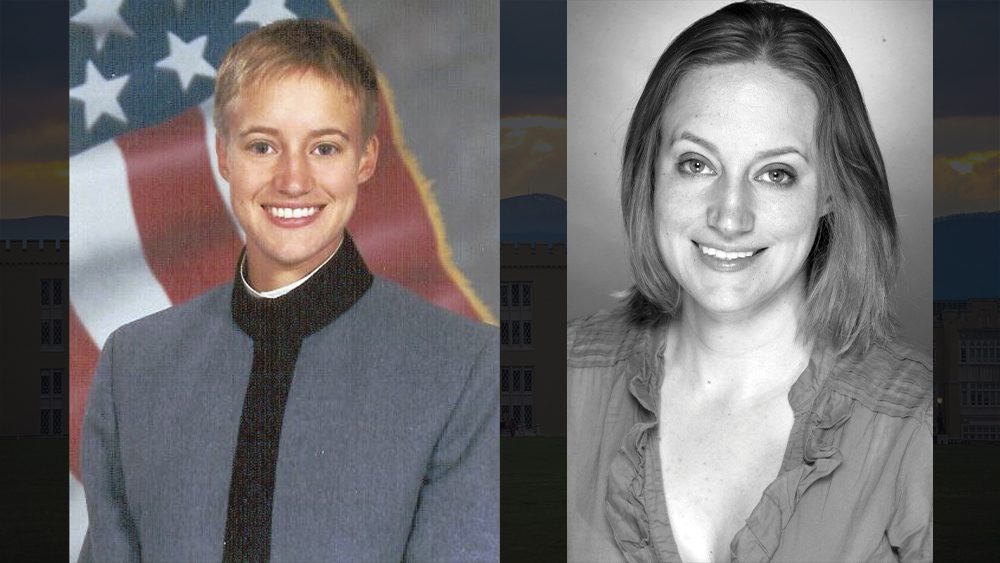

“If the Rat Line was the hardest thing I’ve ever done, the apprenticeship was the second hardest,” she said. In 2019, after over a decade of working for various patent firms, she moved to her current position at STMicroelectronics. Here, she has returned to her first love, microelectronics, and is able to explore the client side of the process.

It was on the VMI post that she first learned about microelectronics. Her work involves “everything that’s very, very small,” she said, explaining that the field encompasses things like computer chips (microcontrollers), memories, wireless exchange protocols for smartphones and the Internet of Things, and the process of fabricating chips in clean rooms. A distinguished graduate, she majored in electrical engineering with a minor in mathematics and a concentration in microelectronics. Her education was funded through a VMI Foundation scholarship.

Throughout her cadetship, she had support from some usual sources—like her dyke and a host family—and a somewhat unexpected source.

Her dyke, Steve Pruitt ’98, and his roommates “were a huge help.” Her host family, Col. William and Nancy Lowe, “adopted” Portavoce. Lowe teaches math at VMI. Like so many families in the Lexington/Rockbridge community, the Lowes opened their home and gave a young cadet respite from VMI. “They would take me to their house and feed me a regular home-cooked lunch [and] let me take a nap and a bath.”

The unexpected source was Col. L. VanLoan “Van” Naisawald ’42. He wrote several books and sometimes gave speeches to cadets, including at the Class of 2001’s New Market ceremony at the end of Matriculation Week. He spotted Portavoce in the crowd and asked to speak with her. He asked her the usual questions, like what she was studying and where she was from. Slightly dazed from Matriculation Week, she answered. He gave her a short speech, along the lines of “Go get ’em, gal—give ’em hell!” All through Portavoce’s cadetship, “Uncle” Van would come to football games, visit Portavoce, and bring her treats.

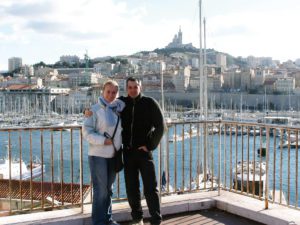

Portavoce and her husband, Alain, in Vieux Port, Marseille, France. Portavoce met her husband, who is French, while both were studying at the University of Virginia.

Following VMI, she wasn’t exactly sure what path she wanted to take. She considered pursuing a doctoral degree and teaching—maybe at VMI. She went to the University of Virginia and earned a Master of Science degree in electrical engineering, focusing again on microelectronics. At UVA, she met her husband, Alain—a native of France—who was completing physics postdoctoral studies. After finishing, he returned home to France. Portavoce was able to follow him six months later.

She arrived in her new country on a student visa and took rigorous courses in her new language. After the couple married, she was able to change her status, get a residency permit, look for work, and eventually gained French nationality. She then found a job as a project manager—and found she didn’t like it very much. “I was basically hired because I spoke English and spent my days haggling with suppliers.”

She kept looking for different options and learned about innovation and patents. She sent her résumé to every single patent firm in her area—10 firms in all. Nine said no, but one agreed to take her on as an apprentice.

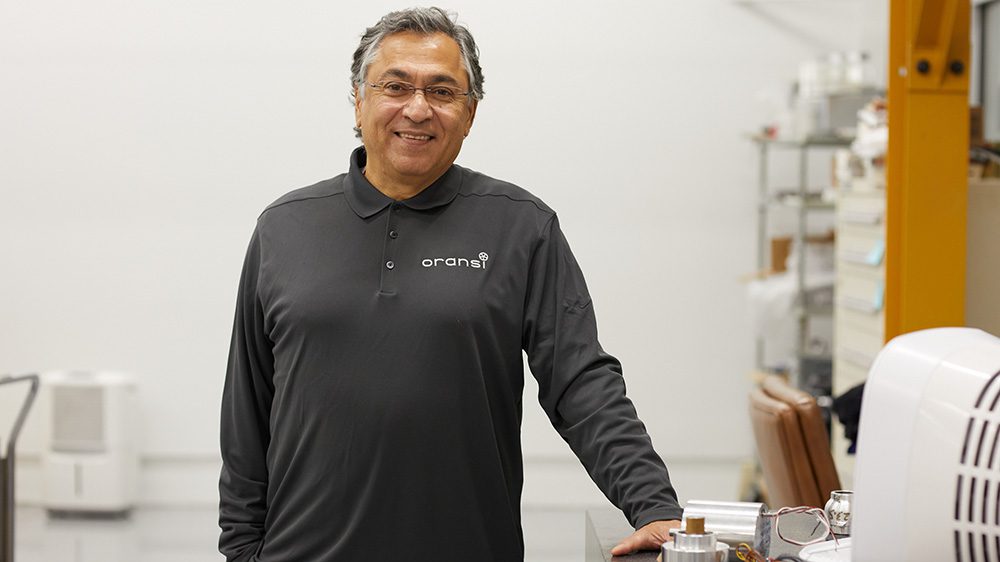

The Centre d’Études Internationales de la Propriété Intellectuelle (in English, the Center for Intellectual Property Studies) in Strasbourg, France, grants intellectual property law degrees. All patent attorneys must have a science or engineering background upon which a legal foundation is overlaid. At the time, Portavoce did not have this degree—which is why most of her job applications were turned down. The firm that did hire her had a big microelectronics client, STMicroelectronics. They liked her specialized experience and education—and speaking English didn’t hurt.

She completed an accelerated version of the patent law degree while working fulltime and later passed exams, earning licenses in both the EU and in France, as well as passing the U.S. Patent agent exam on the side. Aside from certifying her as an expert, Portavoce was able to defend clients before the Boards of Appeal of the European Patent Office, which deals with the validity of the European patent.

Years later and thousands of miles from barracks on France’s southern coast, Portavoce spends her days immersed in a paradox. Patents (temporarily) restrict the result of one of the most unfettered human attributes—ingenuity. They are the result of an adversarial system—an exacting method that begets excellence. Portavoce’s day-to-day affairs echo a small college on a hill in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley where Portavoce began her post-secondary education and where another type of adversarial system results in excellence.