The 13th Annual VMI Leadership and Ethics Conference, “Principled Dissent: Navigating Moral Challenges,” was held Monday, Oct. 31, and Tuesday, Nov. 1, in Marshall Hall. The conference focused on both the personal aspects of developing and exercising moral courage and the organizational environment set by leaders to encourage respectful, honest, and candid conversation.

More than 160 participants, including students from many colleges, universities, and military academies from across the nation, as well as many VMI cadets, gathered to hear inspirational speakers, participate in collaborative activities, and network. Attendees came from schools including Virginia Tech, Christopher Newport University, Washington College, The Citadel, the Coast Guard Academy, Texas A&M University, Norwich University, the U.S. Air Force Academy, and East Tennessee State University.

Central to the conference’s programming were small group discussions and speakers focusing on critical thinking, problem-solving, making ethical decisions, and becoming an effective leader with conviction.

Maj. Gen. Cedric T. Wins ’85, superintendent, welcomed attendees Oct. 31 and challenged them to learn how to lift their voices to the world’s challenges while exploring the dimensions of effective leadership, often placing courage over comfort. “There is a fine line between constructive and destructive dissent. Over the next two days, you will learn new skills on how to speak up and be critical when the situation is appropriate. You will learn about yourselves and how you, as leaders, can effectively influence a team and encourage a culture of honesty and integrity,” Wins said.

Ira Chaleff, the first guest speaker, is an executive coach in the greater Washington, D.C., area and author of the book, “The Courageous Follower: Standing Up to and for Our Leaders,” which is used widely in leadership studies and development programs. His later book, “Intelligent Disobedience: Doing Right When What You’re Told to Do Is Wrong” was named the best new leadership book of 2015 by the University of San Diego School of Leadership and Education Sciences.

Having recently recovered from an illness, Chaleff spoke remotely to his audience, taking as his topic “A Critical Leadership and Followership Skill.” He defined leadership as “a relationship of mutual influence between leaders and followers” and noted that in every organized activity, there is a leader and at least one follower. Sometimes one leads, and sometimes one follows. He stated that followers are equally as important as leaders when all share the same values and are in service to a common purpose. To follow courageously, one should stand up to and for the leaders; sometimes, a leader should be challenged or questioned.

Chaleff discussed the idea of “intelligent disobedience,” which is resistance to an order if the leader lacks legitimate authority or the order will produce harm. He gave an example of a guide dog for the blind being taught to disobey commands when they pose a danger. The dog’s visually impaired master has legitimate authority but may give the command to lead him across the street. At that point, the dog intelligently disobeys. Why? Because what the master doesn’t realize is that a quiet car is quickly approaching, and if the dog obeys, he will put himself and his master in grave danger. He noted that this type of disobedience differs from civil disobedience, where the system is perceived to be unjust, with violations of laws and rules committed, usually to bring public harm.

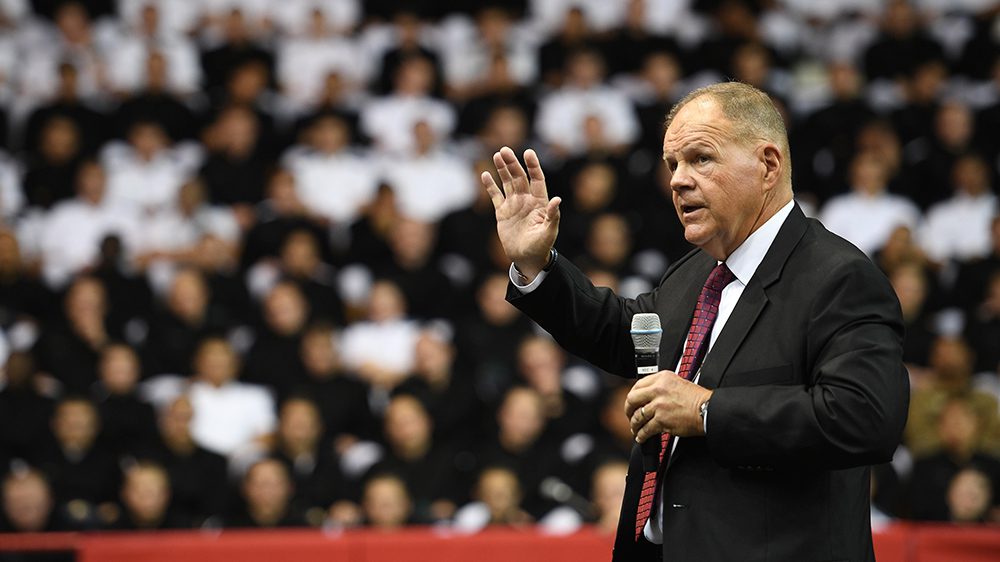

Erika Cheung, who is known for being a key whistleblower reporting the medical-diagnostic company Theranos to health regulators, addressed conference participants in Gillis Theater.—VMI Photo by H. Lockwood McLaughlin.

Chaleff discussed authority structures, which are externally assigned roles, for example, a job description or responsibility flow chart which clarifies who can set policy or issue orders for others. Such structures promote orderly group activity and efficiency. Sources of internalized rules are often established at a young age and can come from family, schools, youth programs, religion, culture, indoctrination, and organizational norms. Varying internalized rules can inhibit the flow of information and ideas. The speaker noted there are varying degrees of obedience. Some people obey authority, even to the detriment of themselves and others, while others limit their obedience when it conflicts with that of a higher authority: For example, what they were taught by their parents, or what their religion or conscience forbids.

Chaleff advised using an assertive voice when dissenting. An assertive voice is assured, confident, firm, and forthright. A mitigating voice is diplomatic, hedging, and weak. A mitigating voice may be appropriate in some circumstances, but the closer to risk or danger a situation comes, speakers must change their voices to convey assertion. Chaleff gave a real-life example of a co-pilot who was concerned with the pilot’s landing approach but only used a mitigating voice and deferred to the pilot’s experience and authority. Even to the point immediately before the airplane crashed, the co-pilot continued to use a weak voice, to the demise of everyone on board.

In closing, Chaleff recommended that when one is contemplating intelligent disobedience, to first observe the risk, pause the action, resist obeying or conforming, use an effective voice, counter-pull if needed, find better alternatives, then return to lead as appropriate, since taking away leadership from the authority is not the goal, but rather advising and correcting toward the common purpose.

The next speaker was Erika Cheung, who began her career as a medical researcher in the biotechnology industry and later became a key whistleblower reporting the medical-diagnostic company Theranos to health regulators.

Theranos, which was started in 2003, was thought to be the latest new company in Silicon Valley whose value would skyrocket. The company claimed to simplify blood testing with one simple finger stick rather than the traditional blood draw of multiple test tubes from the vein of an arm. The company claimed to have a machine that could provide test results within an hour, and its founder, Elizabeth Holmes, was thought to be the Steve Jobs of the healthcare industry. Holmes was successful in raising $700 million to start the company and was able to put together a high-profile board of directors, including Henry Kissinger, George Schultz, and retired U.S. Marine Corps Gen. James Mattis.

When she was hired at Theranos, Cheung was 22 years old, fresh out of college. She was drawn to Theranos because of its claim to make healthcare more affordable, especially to people without health insurance. But Cheung immediately noticed problems. Having only worked for about a month, Cheung described an incident that she called the “Thanksgiving Nightmare,” in which she tried to run a quality control test on the machine but kept getting conflicting results. When she reported the problem, she was told she was too inexperienced to run the test properly.

She soon discovered that the blood tests were not being run in the new machine but in the traditional FDA-approved machines secreted in the building’s basement. When FDA regulators sent trial blood samples to test the integrity of the new Theranos machine, the samples were tested both in the new machine and the traditional machines, but the test results from the traditional machines were sent back to the FDA regulators.

Cheung observed this fabrication and chose to resign rather than join in the lie. Later, she wrote a letter to regulators, which started the investigation. Criminal charges were filed against Holmes and Sunny Balwani, who served as chief operating officer for the company. They were both found guilty, and sentencing is pending.

Cheung is now executive director of Ethics in Entrepreneurship, a nonprofit organization that aims to embed ethical questioning, culture, and systems in start-up ecosystems worldwide.