Anyone who attended VMI from 1956-60 knew this mustached, ramrod straight, energetic, and positive soldier whose World War II fame preceded him, and a now-famous Life Magazine photo was yet to come. Glover Johns, Class of 1931, was a proud Texan from Corpus Christi. His father, Class of 1908, had been tossed from VMI for his “hell raising,” but his uncle graduated in 1915. Another uncle, Randolph Coleman, was Class of 1921 and the father of the actor, Dabney Coleman ’53. Coleman was Johns’ first cousin.

Johns went to VMI because his father thought VMI was the best school, even though he graduated from West Point. At VMI, Johns excelled at rifle and pistol marksmanship, ran cross-country, and graduated with a degree in chemistry. Upon graduation, he was barely 19 and too young for the ROTC commission he had trained for. Instead, Johns joined the Army Reserve.

His nickname was “Major.” As a youth, he had a dog named Sergeant, and his father thought it fitting that he outranked the dog, so he was called Major. Following graduation, Johns studied in Germany for a semester, married, had a son, later divorced, and worked in a boring job for an alkali company in Texas. In the late 1930s, he worked for the Chamber of Commerce in Corpus Christi and wrote a column in the local paper, calling himself “The Major.” By this time, Johns switched to the Texas National Guard and was called to active duty in 1940. This was just before the U.S. entered World War II. Johns was commissioned in the cavalry and sent to Costa Rica, then Mexico—both with the attaché office. He used every connection to get a combat assignment, ending up with the 29th Infantry Division. This was the Blue and Gray Division, which included a lot of Virginians.

Johns landed with the 29th Division Headquarters late in the day on Omaha Beach, D-Day, June 6, 1944. He was a liaison officer from headquarters to troop units. This meant searching for units to get reports during close combat. He had a hairy experience driving into a platoon of resting Germans, then reversing direction in his Jeep and retreating at high speed. The Germans were slow to return fire, but Johns fired at them with his carbine and then with his .45 pistol.

The 1st Battalion, 115th Infantry Regiment, one of nine battalions in the division, had its commander killed June 7. The replacement commander was relieved for lack of aggressiveness. Maj. Johns, without the usual lieutenant colonel rank, was sent to take over the battalion a week after D-Day.

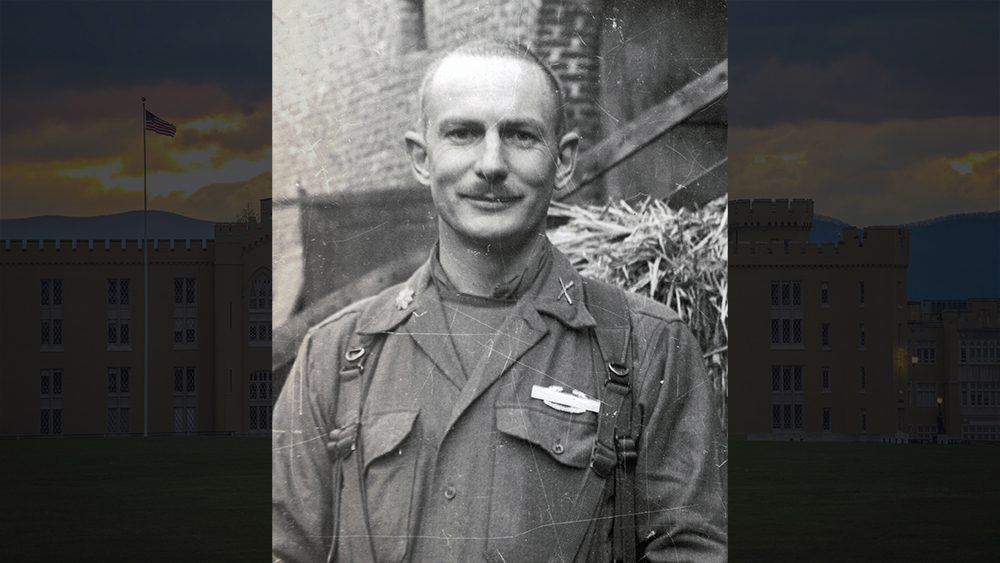

Glover Johns, Class of 1931, as a VMI cadet.—VMI Archives Photo.

Johns was to operate in the hedgerow region of Normandy, where individual fields were surrounded by bushes—typically 6 feet high and 4 feet thick—with trees growing out of them. So, every field was its own fort. The Germans had these fields covered with machine guns, artillery, and mortars. Each field was a battle, and casualties were high. Johns’ first day was memorable, as he lost two radio operators and three members of his staff. German snipers were having a field day, and he was under constant enemy mortar and artillery fire. At one point, he looked down at a young lieutenant on his staff and saw a familiar ring. He was Herb Martin, Class of 1938, his artillery officer. Martin stayed close to “Major,” as this war was ruled by artillery.

At times, Johns had to beg, plead, and threaten his officers to gain even 500 yards. He felt he had to move around a lot to all his units to show courage as an example for his men. Not many commanders were as bold. Johns lost 225 of his 650 men in one day, July 11, when 400 elite German paratroopers counterattacked and broke through his lines. Johns used rear echelon men like cooks and mechanics, plus artillery, to wipe out pockets of Germans in his rear area. Over the next month, Johns was continually engaged in combat as his regiment drove toward the town of St. Lo in northwestern France. Once reaching the town, he split his companies to secure key points and high ground. This was a huge battle, and the 29th Division lost more soldiers in the fight for St. Lo than on Omaha Beach.

Once in St. Lo, Johns set up his command post in a cemetery mausoleum. It was made of 18-inch thick marble and provided good protection. That made news back home. To help him take the city, a tank destroyer was assigned to him. This was a Sherman tank chassis with a 3-inch gun, thin armor, and an open turret. They were designed as fast tank killers. Johns needed it to take out German strong points.

In St. Lo, Germans were everywhere, and the firing was intense. A mortar hit the tank destroyer, and its young commander lay on the ground. Johns raced out to him and flipped him over. He was dead. On his hand was a VMI ring. He was Capt. Sydney A. Vincent, Class of 1940. Johns never met him until then. Vincent is buried in the Normandy Cemetery and earned a Silver Star and Purple Heart.

During World War II, Johns earned three Silver Stars, two Legions of Merit, two Bronze Stars, and a Purple Heart. His victory at St. Lo would allow Gen. George S. Patton, Class of 1907, to enter the war with his Third Army. Johns would continue to command his battalion until the war’s end in May 1945—totaling 11 months in command. Few commanders lasted as long. The intensity of his combat is described in Johns’ book, The Clay Pigeons of St. Lo, published in 1958. This book should be required reading for a description of small-unit combat. By the war’s end, Johns’ unit had lost nearly 2,400 men, more than two-and-a-half times his unit strength.

After the war, Johns married Rita LeCoyer, had two sons, and was posted to attaché jobs in Bulgaria and Turkey. When the Korean War was on, he wanted to join the fight and earned himself command of the 224th Infantry Regiment, 40th Infantry Division. This was in the last months of combat in the Korean War. His regiment covered a portion of the infamous Punchbowl region of Korea. Johns was always the inspirational leader, leading from the front. After Korea, he served as an attaché to Formosa (what is today Taiwan) and was beloved by the Chinese there.

After attending the Army War College, Johns was assigned to VMI Army ROTC in 1956 and from 1957-60 as its commandant. Si Bunting ’63, then recently discharged from the Marine Corps, remembers meeting Johns for the first time as an incoming rat in 1959 and was so impressed. He looked, “every inch a soldier,” said Bunting. Johns, a colonel, told Bunting, a cadet, to see him the next day, so Bunting reported to the commandant’s office. Johns told him to relax and offered him a cigarette. The commandant told Bunting that prior service cadets did poorly because they had big egos, and they became cynical of the VMI system. He told Bunting not to get cynical. Then Johns ordered him to put out the cigarette, salute, and get out. “I do not want to see you until after the rat year,” Johns said. Most cadets remembered Johns as a great commandant who enjoyed being with cadets. He could be fun yet authoritative.

Col. Glover Johns, Class of 1931, with Lyndon B. Johnson in West Berlin. From left are Lucius D. Clay, former military governor of Germany and one of the people credited with the success of the Berlin Airlift; Johns; Johnson; and Walter C. Dowling, then-U.S. Ambassador to West Germany.—VMI Archives Photo.

In 1960, Johns took command of the 1st Battle Group, 18th Infantry, 8th Infantry Division in Germany. This was a brigade-sized command. Barely had he taken command when the Russians and East Germans started sealing off West Berlin. Too many East Germans were fleeing west, so barbed-wire barriers were set up, and later the Berlin Wall. This violated the Potsdam Agreement following World War II. President Kennedy needed to show the Russians U.S. resolve, and Johns was tasked to lead his Battle Group’s 1,500 men past Russian forces through East Germany to Berlin. This was a tense time. National Guard and reserve units had been mobilized, and the entire U.S. military was on alert. Johns could become the catalyst for the start of World War III. Instead, he led his soldiers successfully, never hesitating, at times having tense standoffs with the Russians. When he arrived at the Russian/East German checkpoint outside Berlin, Johns spoke in fluent German to the guard and ordered the gate to be opened. The guard replied in German, saying, “What if I don’t?” Johns pulled out his .45 caliber pistol and replied, “Then you will be the first casualty of World War III.” The guard opened the gate, and Johns was soon swarmed and welcomed by thousands of West Berliners. Johns called the White House when he arrived in West Berlin, and he was met by Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson. Years later, his cousin, Coleman, asked Johns what would have happened had the border guards refused to admit the Americans into Berlin? Johns replied confidentially, “We would have given them a hell of a show.”

Following the Berlin incident, Johns’ photo appeared in Life Magazine. After seeing it, Johns said he had not slept in two days. Col. David Hackworth, likely the most decorated soldier of the Vietnam War, worked for Johns, Later, when writing his book, About Face, Hackworth remembered Johns’ principles of leadership. These principles came from more than 30 years of service and two wars. My favorites are the first and the last. “Strive to do small things well … and stay ahead of your boss.” This is great advice in business, as well.

I asked Coleman, who was very close to his cousin, what stood out about Johns? He said, “He has intense eyes, and he was a handsome man who enamored people when he entered a room.” Coleman also recalled that Johns’ rifle and pistol skills were legendary. He once demonstrated this by shooting through a quarter when it was tossed in the air, proving to a soldier that his rifle worked.

Johns concluded his Army career as attaché to Spain. He was well suited, as he spoke fluent Spanish along with German, French, and Bulgarian. He retired in 1964 to Austin, Texas, and was a technical adviser for the movie Patton. Johns died from cancer in 1976. His ashes were spread at VMI. He clearly impacted many VMI alumni and is one of the VMI greats of the 20th century.

Author’s Note: This article was written by Jim Dittrich ’76, the VMI Alumni Association historian. His research came from the VMI Archives, and the book, The Clay Pigeons of St. Lo, by Glover Johns Jr. ’938. Thanks to Dabney Coleman ’53 and Gen. Josiah Bunting ’63 for their memories.