If you attended VMI between 1952–85 and ventured into the history department at Scott Shipp Hall, you may remember Maj. (later Col.) Tyson Wilson. Cadets affectionally called him “Ty Ty.” What you may not know is that he participated in five major combat campaigns in the Pacific during World War II.

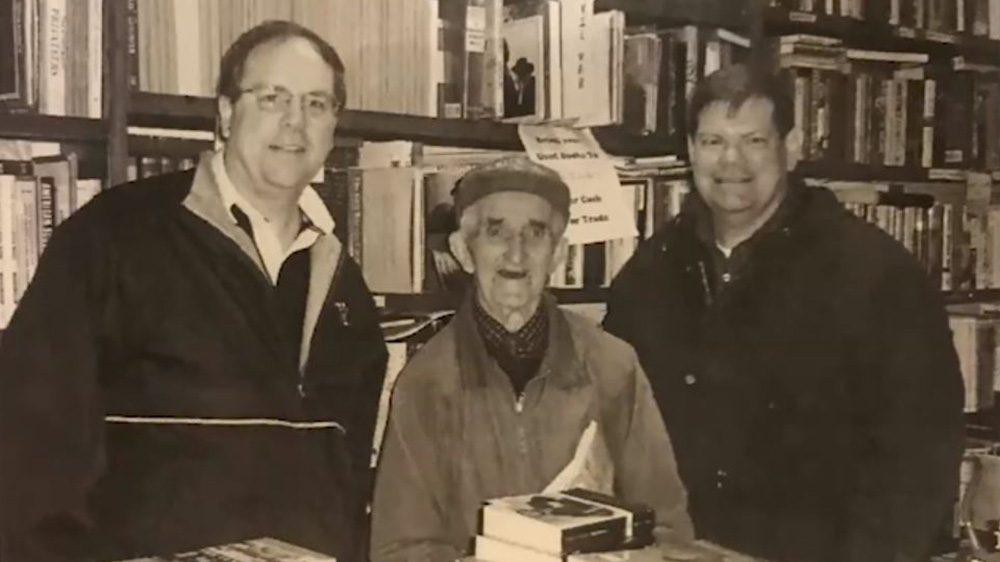

Jim Joustra ’76 and I ran into Wilson in a Lexington bookstore in 2004. I was looking at a book about U.S. Marines in the Pacific during World War II, and Wilson said, “I was there.” We talked, and he related a little of his service in the Marines during the war. I asked if I could visit him and tape his memories for the VMI Archives. Between 2004 and Wilson’s death in 2011, I visited him often and recorded his memories, which are now in the John Adams ’71 Oral History Collection within the VMI Archives.

Wilson was born in New York City, New York, in 1918. One of his earliest memories was of Charles Lindbergh’s parade down 5th Avenue in 1927. Lindbergh was a national hero and the first pilot to fly across the Atlantic Ocean. Wilson’s dad managed a laundry machine company in New York City, and Wilson watched Lindbergh’s parade from his dad’s office window. Sadly, Wilson’s dad died the next year, and Wilson and his mother lived frugally.

Wilson was an Eagle Scout and later an acting scoutmaster. Scouting was an important part of his life. Wilson graduated from New York University and was pursuing a master’s degree at Yale University when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Like almost everyone in the “Greatest Generation,” Wilson went to the recruiter to join the war. He was initially rejected for high blood pressure, but his doctor gave him a pill, and magically, he was accepted into the U.S. Marine Corps.

Wilson started out as a truck platoon leader in the engineers but talked himself into an infantry unit as an extra or 6th lieutenant. His first unit was A Company, 1st of the 8th Marines. The other lieutenants were mustangs, meaning they were promoted from the ranks.

Wilson’s unit was sent to Guadalcanal, the first great battle in the Pacific War. U.S. Marine Corps Lt. Col. Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller, Class of 1921, and Sgt. John Basilone, Medal of Honor recipient, were serving in sister battalions. Wilson could hear the Japanese yelling, “Die, Marine,” and watched some aerial dogfights. Wilson’s initial combat was intense, and soon his commanding officer, executive officer, and the other five lieutenants were either killed or wounded. Wilson was given command, and during his first day in command, he was wounded by shrapnel in the shoulder and leg. He was evacuated to a ship offshore.

Wilson liked to tell this humorous story. As he related, ships had funnels that pulled the hot air from the holds via fans. Some jokester on his ship hooked the toilets to these fans, sucking the toilet residue through the funnels and the “$@#! hit the fan.” Wilson insisted this is where that expression came from, but I cannot verify this. He was outside on deck, observing this firsthand when it occurred.

After Guadalcanal, his unit was attached to the 2nd Marine Division training outside of Wellington, New Zealand. Wilson was assigned to his battalion S2 (Intelligence) section as he could no longer carry a rifle due to his wounds. During that period, Wilson was introduced to a pretty New Zealand Army Women’s Army Corps service member named Lois Ramsey.

Wilson asked if he could call on her. She agreed and directed him to get off at the last tram stop in Wellington, which she lived two houses away from. Wilson followed her instructions but realized he didn’t remember her name. He had to ask around when he got off the tram. Despite the initial setback, these two hit it off, and Wilson knew he was hooked and quickly proposed, knowing he was deploying soon. Lois accepted, but Wilson had to go through the Marine chain of command to get marriage approval. This included stops at the battalion, regiment, and division levels. That was the easy part, as he had to get approval from the Anglican bishop of Wellington, who finally approved.

Wilson wouldn’t see Lois for another two years, but he was smitten for the next 60 years. They were married in August 1943, just before he shipped out for Tarawa.

Tarawa was an L-shaped coral island with a portion called Betio at one end where the Japanese were dug in deep with their Nambu light machine guns. Wilson said they were excellent weapons.

Many of the Marine Amtracs were caught on the coral, and they had to wade in under fire, causing hundreds of casualties. Wilson’s boat was also hung up, and his small frame may have saved him, he said. While knocking out Japanese bunkers, he collected intel by tossing grenades or stuffing lit rags down their breathing tubes. Three thousand one hundred Marines were killed or wounded on Tarawa.

When I asked what leader impressed Wilson the most, he said, “Colonel Dave Shoup, by far.” Shoup won the Medal of Honor on Tarawa. Later, he was Marine Corps commandant.

After a rest and more training on the Big Island of Hawaii, Wilson’s next assignment was Saipan. While there, Wilson was part of Division G2 (Intelligence) and collected intel while observing another tough fight. Near the end of the battle, the Japanese forced the local people to jump off the Point Marpi cliffs to their deaths. Many of Wilson’s friends shared their stories of horror with him.

There was no break after Saipan, as the 2nd Marine Division was sent to take the island of Tinian. Tinian was later used to fly the two atomic bombs to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. First, they had to take the island, and the Marines were initially held up by heavy Japanese fire.

Wilson volunteered to climb a radio tower to report on enemy positions. This tower was under enemy fire, and Wilson heard the rounds pinging around him. He carried a radio and a map. During one call, Maj. Gen. Thomas E. Watson, division commander, spoke with Wilson, who provided essential information. Wilson had to stay up the tower all day, and only night allowed him to climb down. Watson later awarded Wilson with a Bronze Star with a “V” device for valor.

The biggest battle was yet to come—Okinawa. During the battle, Wilson collected intel and stopped by the 10th U.S. Army headquarters. He bumped into U.S. Army Lt. Gen. Simon B. Buckner, Class of 1906, the commander on Okinawa, who asked him to sit. They talked for about 30 minutes. Wilson had never talked to such a senior general. Buckner attended VMI for a time before heading to the U.S. Military Academy. His father was a famous Confederate general during the American Civil War.

Soon after their initial meeting, Wilson was standing near Buckner, observing the battle, when a piece of shrapnel hit Buckner. Wilson helped load him into a jeep for evacuation, but he knew the general would not survive. Buckner was the senior general killed in the Pacific and was posthumously promoted to general.

After Okinawa, Wilson returned to the U.S. and had the challenge of finding Lois. He knew she was on a ship heading to a Gulf port via the Panama Canal. Using his intel skills, Wilson discerned which port, and somehow, they linked up. One of the first stops was to meet Wilson’s mom, who liked Lois immediately. Sadly, his mom died soon after.

Wilson’s life after the war led him back to Yale to finish his master’s degree, and he started doctoral work at Columbia University. While researching a project, he stopped at VMI and met William Couper, Class of 1904, VMI historian, who hired Wilson on the spot. Wilson never finished his doctorate.

Wilson spent the next 33 years at VMI teaching economics, history, and in the ROTC department. He taught military history to many alumni. Wilson was devoted to his cadets, serving as class advisor three times, a TAC officer, and advisor to many cadet clubs and organizations.

Wilson counseled every cadet in the classes he worked with. He also has many commendations in his VMI Archives file from all five of the superintendents he served under. Wilson was eventually promoted to colonel at VMI for academic achievement before he retired in 1985. He continued in the Marine Corps Reserve, culminating with 37 years of service. He retired as a Marine colonel.

Wilson spent his later years caring for Lois, who developed Alzheimer’s disease. Lois passed away before Wilson, leaving behind their two grown daughters. Wilson had a grandson, John Getgood ’98, a U.S. Air Force pilot, whom Wilson was especially proud of.

I visited Wilson in his Lexington home and later at Kendal at Lexington, his retirement home. He read until his final year and received breathing treatments for malaria that plagued him since the war. He said he had malaria five times in the war. Wilson died in 2011 and is buried beside many VMI faculty in the Oak Grove Cemetery, formerly known as the Stonewall Jackson Cemetery.

Wilson’s awards included the Bronze Star for Valor, Purple Heart, Presidential Unit Citation with two stars, and the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign medal with four stars (denoting five awards for his five battles).

Wilson was a down-to-earth man who loved his family, country, and VMI. His example sets him apart from many, and he should be remembered as a dedicated Marine and professor.

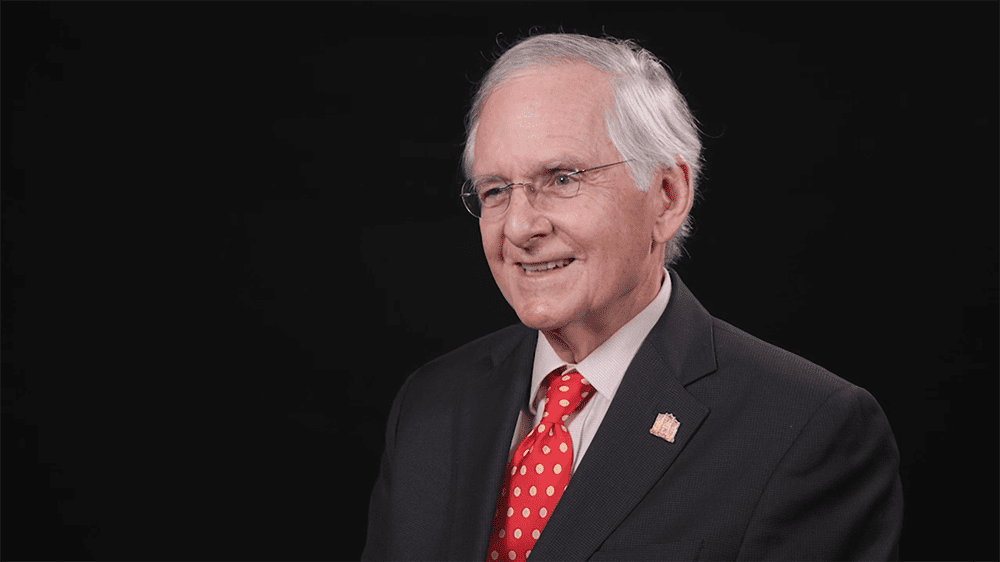

Editor’s Note: Jim Dittrich ’76 is the VMI Alumni Association historian. He lives in Williams-Junction, Arkansas, near Perryville.

-

Jim Dittrich ’76 VMI Alumni Association Historian