Albert Einstein said, “Nothing happens until something moves.” While he likely meant to apply that observation to physics, it is now closely associated with the fields of logistics and transportation. This is so because it is true. Unless people and materials of all kinds move somewhere, no human endeavor is possible.

Since the early 1990s, Christopher Caplice ’84, Ph.D., has devoted his professional life to ensuring that a lot of things – well, almost everything – move and that they move more efficiently. In fact, thanks to his contributions to the fields of transportation and logistics systems, whenever you see a truck on a highway or a delivery van in your neighborhood, you can be sure that Caplice somehow influenced how it is being used.

His interest in transportation and logistics was piqued by his service as an Army Corps of Engineers officer. “I was applying my degree in civil and environmental engineering by building roads, airfields and other things in Germany. But over time, I became more interested in how things operate on roads than in the construction of them.”

Yet he did not immediately plunge into the field in which he would later immerse himself. First, after leaving active duty, he pursued a master’s degree in civil engineering at the University of Texas at Austin (where his adviser happened to be C. Michael Walton ’63).

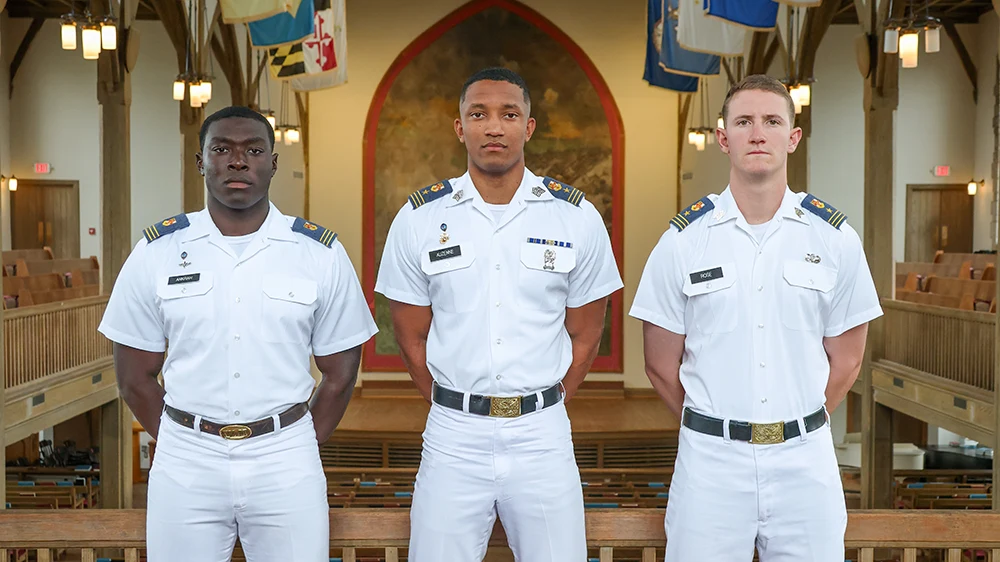

He then returned to VMI to be a sub-professor and TAC officer for two years with the intention of seeing if an academic career was for him. “The best thing about coming back to VMI as a sub-professor was being able to work with some of my former professors – Colonel Don Jamison ’57 in particular.” One drawback to being at the Institute: “I had a recurring nightmare that, as a TAC officer, I would be running the stick at night, go into a room and come out as a 3rd [Class cadet].”

His second VMI experience convinced him to pursue an academic career, but he eschewed engineering in favor of the field that he had thought about in Germany. “I was drawn to open-ended problems that involved both quantitative engineering challenges and a human behavior component,” Caplice said. “I decided to concentrate my Ph.D. on developing a more systems-oriented approach to transportation and logistics.”

Not long after arriving at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1992, he hit upon his research topic. “MIT’s motto is ‘mens et manus’ – that is, mind and hand – meaning that MIT encourages research that is both theoretical and applied.” In this spirit, Caplice’s adviser suggested he explore how shippers and carriers could form more efficient relationships. “The practice at that time was very confrontational,” Caplice explained, “Every shipper must move goods along what are known as ‘lanes’ – essentially routes between two places, like Chicago to Atlanta. Shippers would select which carriers to use on a lane-by-lane basis on a pure low-cost basis. So, shipper A would ask carriers A, B and C to submit a separate bid for hauling along each lane in their network.”

Caplice’s research demonstrated how treating each lane independently was flawed, as it did not allow carriers to leverage their natural economies of scope. “Economies of scope is an economic concept that the more different-but-similar goods you produce, the lower the total cost to produce each one. If you’re a trucking firm, moving a shipper’s goods along lanes that complement each other reduces the … empty miles driven, increases your operational efficiency and ultimately reduces the cost to the shippers.”

To capture these economies, Caplice developed a procurement methodology that allowed for bidding for sets of lanes and a means to evaluate the bids. Along with increased efficiencies, his approach allowed for the consideration of other nonfinancial factors, such as level of service and minority status, in the process.

When he finished his dissertation in 1996, it struck an immediate and responsive chord. “As luck would have it,” Caplice remembered, “when I graduated, the freight industry was ripe for a change in how shippers and carriers worked with each other.” The Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals presented him with its Doctoral Dissertation Award, and he received an honorable mention from the Transportation Science Section of Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences. That was the “mens.”

Next came the “manus” as Caplice went out and applied his findings, leading a team that established “optimization-based procurement concepts” in more than 50 firms that spent more than $7 billion for transportation. In short order, his concepts became the industry standard throughout the United States.

In 2003, Caplice returned to MIT to run the master’s program in supply chain management as part of the Center for Transportation and Logistics. In this new position, he could continue his research, examining more closely some foundational aspects of freight transportation. “Academic research,” he explained, “often comes up with solutions and approaches that practitioners, with their day-to-day concerns and obligations, cannot.”

Seeing the need for more in-depth research, he formed MIT FreightLab as part of the CTL in 2008. “FreightLab’s objective is to keep pushing the boundaries of how freight transportation networks can be designed, procured and managed.” In it, about a dozen master’s and doctoral students and research scientists explore issues like truck driver shortages and forecasting freight demand. FreightLab also organizes workshops and roundtables and completed almost two dozen research projects with partner companies and organizations, like the U.S. Department of Transportation and Walmart. “While our projects’ theoretical contributions are interesting, the practical impacts are more satisfying,” said Caplice. “The methodology we developed for the federal government has been adopted by several states as part of their transportation planning process, and Walmart has saved millions of dollars each year by applying our research.”

It’s an old saying that, if you want something done, find a busy man. It’s hardly surprising then that, in 2014, MIT asked Caplice to create a single Massive Open Online Course in supply chain management based on the course he regularly teaches on logistics systems. The course ended up with more than 30,000 registrants in its vey first run. This demand led Caplice to create four additional courses under the Supply Chain Management program.

Success begat success, and in 2015, Rafael Reif, MIT president, designated these courses as the school’s first MicroMasters credential program. While a MicroMasters is a stand-alone accreditation, it can lead to a master’s degree at MIT – the first time MIT has ever given academic credit to an online course. If a MicroMasters credential holder is accepted into the Supply Chain Management program, he or she will be granted a semester of academic credit and, thus, can complete the degree in five months instead of 10. The MicroMasters is also recognized by other colleges for credit in their graduate programs.

Even for someone who is accustomed to thinking globally, the program’s reach has impressed Caplice. “In my 17 years of teaching at MIT, I’ve taught maybe 1,500 students. As of July 2020, through the online MicroMasters program, I have reached more than 400,000 learners from 196 different countries. They include people as young as 15 and as old as 80, military members and stay-at-home parents. It has been very exciting to be part of the wider democratization of education.”

While running these programs and continuing his research take up a lot of Caplice’s time, his mind is never far from the industry which he has significantly helped reshape for more than two decades. “Freight transportation has changed dramatically over the past few decades, especially in the United States – from deregulation in the 1980s, to the adoption of optimization-based decision support tools in the 1990s, to the introduction of the internet in the early 2000s and finally to the widespread adoption of automation, artificial intelligence and mobile computing today.”

Asked what makes the industry so compelling, he gave several reasons. “First, it is massive, representing roughly 9% of national gross domestic product and employing about 5 million people. Second, it is exceptionally dynamic with new firms entering and exiting – especially in the realm of full truckload transportation. Third, it is an exceptionally competitive industry. Fourth, every transaction involves at least two, and usually more, independent players with differing objectives and goals. Finally, because there are so many different players and the costs are so important to shippers, there is a huge appetite for testing and adopting new ideas. Adding this all together creates an exceptionally fertile area to develop new concepts, apply them and observe the impact.”

The industry’s technological sophistication is something that Caplice wants people to appreciate more. “People see trucks on the road and think, ‘That’s sophisticated?’ Well, the technology required to ensure that the right products are in the right vehicles and delivered to the right locations at the right time at an acceptable cost is amazing. Even just 20 years ago, the level of analytical horsepower in the industry was quite low. Now, it is rare to find a trucking or logistics company that is not using machine learning, artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things and other technologies.”

According to Caplice, the value of technological advancements of the past several decades have been borne out during the COVID-19 pandemic. While the pandemic did have effects on the supply chain, he says two things should stand out. The first: The supply chain never stopped, and there were never any true shortages. Photos of stores’ empty shelves, he points out, tended to be taken at the end of the day. They were almost always restocked overnight because truck drivers kept moving and distribution centers kept working. The second is how quickly companies adapted. “Supply chains have proven to be exceptionally agile and flexible. Firms realigned production lines, reassessed product assortments and redesigned their supply chain networks on the fly,” he said.

Looking forward, he sees “silver linings” in the pandemic experience. “Companies’ digital transformation now is three to five years ahead of where it normally would have been due to the necessity of working remote and minimizing physical hand-offs. These efficiencies will continue after the pandemic and will pay substantial dividends.”

Caplice wants cadets and alumni to consider transportation, logistics and supply chain management as a career. “While it is an old profession, it is constantly being reinvented,” he said. “Having a military background is a huge help as the demands for operational performance are similar. Finally, it’s an industry that is only continuing to grow.”