In honor of Black History Month, Robert Child, author of the book, “Immortal Valor: The Black Medal of Honor Winners of World War II,” spoke at VMI as part of the Center for Leadership and Ethics’s Courageous Leadership speaker series in Gillis Theater Feb. 19, 2024. The event was co-sponsored by the Office of Diversity, Opportunity, and Inclusion; the Dean’s Academic Speakers Program; and the George C. Marshall Foundation.

Child shared with cadets the valiant and courageous stories of the seven African American World War II soldiers chronicled in “Immortal Valor.” In 1945, Congress awarded the Medal of Honor to 432 recipients, yet not one of the more than one million African Americans who served was among them. In 1997, more than 50 years after the war, former President Bill Clinton finally awarded the Medal of Honor to those seven heroes, all but one, posthumously.

According to Child, the base criteria for the award was that the men had to have been awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the second-highest military decoration for soldiers who display extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force, except Reuben Rivers, who received the Silver Star, the third-highest military decoration for valor in combat.

Through a series of short biographical videos and his own words, Child shared an abbreviated version of the gallant stories of the seven men.

Charles Thomas grew up in Detroit, Michigan, and was midway through his junior year at Wayne University when Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941. He was drafted into the U.S. Army and became part of the new tank destroyer force whose mission was to seek, strike, and destroy enemy tanks. Thomas stood out among his peers with his mechanical engineering aptitude and several years of college behind him. His unit entered the European theater in early 1944 and immediately saw action. Thomas led his company up a foggy road into Climbach, France, five miles from the German border, where German shells hit them. The command car in which Thomas was riding struck a mine, blowing him and several other soldiers out of the vehicle. He was bleeding from wounds to his legs and arms, and several machine gun rounds caught him across the chest. In an interview afterward, he stated, “My only thought was, ‘deploy the artillery, start firing, or we’re dead.’” The battle intensified, and after four hours of combat, three of the tank guns were destroyed by the enemy, and the fourth was out of commission, but the American infantry was able to circle the town, and Thomas was medically evacuated. Col. John Blackshear, who watched the battle, later wrote, “That was the most magnificent display of heroism I have ever witnessed.”

Vernon Baker was raised by his grandparents from the age of 4 after his parents were killed in a car crash. After basic training at Camp Wolters, Texas, he joined the 370th Infantry Regiment at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, was promoted quickly to staff sergeant, and then sent to officer candidate school at Fort Moore [formerly Benning], Georgia. He graduated as a second lieutenant in January 1943 and was sent to Europe, where his unit was tasked with breaking through Hitler’s Gothic Line in Italy in an area called the Triangle of Death. In a later interview, Baker recalled, “The whole regiment was trying to take those hills, battalion by battalion. The first battalion went up, and they got cut to pieces trying to get up there. The second battalion went up and got cut to pieces, and when they were driven back down, it was our turn.” So, on the morning of April 5, 1945, Vernon and his battalion of 26 men made it up to the castle fortress. Baker found out later that his regimental commander had been told that his men had all been wiped out, so no reinforcements were sent. Baker remained with his battalion to secure the strategic German castle fortress. He lost 19 of his 26 men. He was the only living Black recipient of the seven selected to be awarded the Medal of Honor at the White House. He told CNN after the ceremony, “I still don’t feel like a hero. I just feel like I was a soldier, and I did my job.”

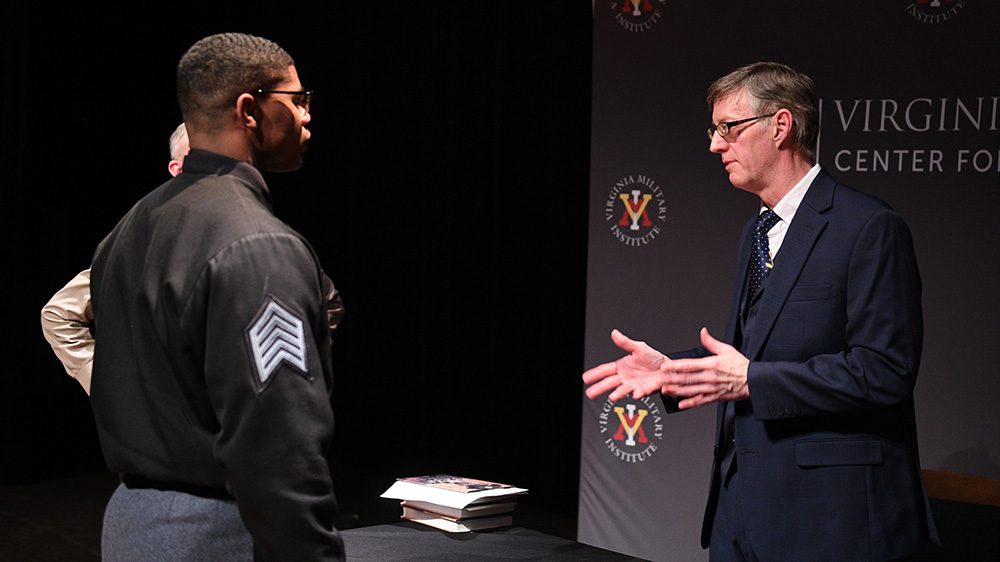

Robert Child signs a copy of his book following his presentation.—VMI Photo by Partridge.

Willy James Jr. grew up as the only child of a widowed mother, and was drafted into the Army in 1942. In the aftermath of the Battle of the Bulge, the Allies were faced with shortages of men due to attrition. The oversupply of Black soldiers serving in supply units was matched by the undersupply of white replacement soldiers for rifle companies on the front lines. James was one of more than 2,200 Black soldiers selected for an expedited four-week training course at the Ground Forces Reinforcements Center in France. He became a scout with the 413th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Lt. Arman J. Cerebella. In March 1945, James’ platoon was part of a convoy rolling from Cologne into the Rhine Valley. Crossing the Rhine River, they met and fought through stiff resistance, but in the village of Lippoldsberg, they faced their greatest test April 8, 1945. James was sent ahead to scout the German positions and reported back to Cerebella, who decided to enter the town. Unfortunately, the fog cleared, and James, who was on the opposite side of the road as Cerebella, cautiously moved forward, constantly checking on his commander. Suddenly, James heard a German shell about 100 yards ahead and saw that Cerebella had been shot by a sniper. James rushed to him and tried to pull him to safety, but he was cut down by machine gun fire. The heroism and sacrifice inspired the remainder of the platoon to push the armor forward.

Edward Carter Jr. was born to missionary parents and was raised in India and Shanghai, China. When Japanese forces attacked the International Settlement in Shanghai, Carter ran away from home and joined the Chinese Army when he was 15 years old. He demonstrated both his marksmanship and bravery, but a month into his service, Carter’s father arrived to take him back home. When his family returned to the United States, Carter enlisted in the Army and was assigned to Gen. George S. Patton’s mystery division force, which headed into German territory after removing all uniform insignia and vehicle markings. Carter soon learned how exceptionally dangerous this mission was in March 1945. Carter and his squad heard the ear-splitting recoil of a Panzerschreck, the German version of the bazooka, from a nearby abandoned warehouse. He immediately volunteered to lead a three-man squad in a dash across the field to the warehouse. One soldier behind him was riddled with machine gunfire immediately. Carter shouted to the other soldier to cover him as he moved forward, but that man was also struck down. At that point, Carter was too far forward to retreat, so he zigzagged his way forward as German machine gun fire hit him. Despite getting shot, he continued moving forward until the sharp stabbing pains caused him to topple over. Carter, still armed with his Thompson submachine gun, decided to wait the German forces out since he knew they would come looking for him. After two hours, his opportunity came. As a German patrol approached, he pulled the Thompson out, thrust all his weight on his right leg to push himself up, and kept his finger on the trigger. In seconds, six German soldiers fell dead, and the remaining two raised their hands in surrender. Ignoring his pain, Carter held one soldier in front of him and another behind him, using them as human shields to make his way back to the American position. After arriving safely, Carter interrogated the German prisoners in German, which he had learned at Shanghai Military Academy. The POWs cooperated and pointed out hidden enemy strongholds on a map. The accurate information allowed the Americans to advance with minimal loss of life.

George Watson was born to sharecroppers in Mississippi. He had a love of learning and an aptitude for math and was an accomplished swimmer, a skill he would use later in the war. He attended Colorado State University in Fort Collins, and upon graduating in 1942, he was immediately drafted into the Army and sent to Camp Lee, Virginia, to train as a laundry specialist in the Quartermaster Corps. By late January 1943, Watson arrived in the Southwest Pacific theater in Brisbane, Australia. He was assigned to the transport ship, Jacob, ferrying troops, weapons, and other supplies. On March 8, 1943, two squadrons of Japanese bombers, escorted by 12 fighters, bombed the Jacob. The ship was completely ablaze and sinking, and the order was given to abandon ship. Watson, who had swum to a raft, could see crewmen leaping off the ship and others floundering in the water. He left the raft and swam toward them, grabbing them one at a time and pulling them to rafts and other floating debris surrounding the ship. He then saw a sailor waving his arms and trying to keep his head above water near the Jacob, which was almost entirely submerged. Watson swam toward the struggling sailor, but it was too late. The sinking of the enormous vessel created a powerful vortex of suction which dragged Watson and the men surrounding the vessel under the waves into the ocean depths. For Watson’s heroic efforts in saving his comrades, including his commanding officer, he was the first Black soldier to be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Ruben Rivers grew up on a family farm with 11 brothers and sisters in Oklahoma. He was drafted into the Army in 1942 and assigned to the 761st Tank Battalion, and in 1944, they were deployed to France. While advancing on the town of Guébling, Rivers’ tank hit a mine, and his leg was slashed to the bone. Rivers refused all medical treatment, commandeered a working tank, and continued advancing through Guébling, fighting on to the town of Bourgaltroff. His company met stiff German resistance, and his commander, Capt. David Williams, ordered the company to retreat. Over the radio, Rivers was heard saying, “I see ‘em. We’ll fight ‘em!” He fought the Germans so the rest of the company could get to safety. During the encounter, his tank was hit, killing him instantly. Williams attended the White House ceremony in 1997 with the Rivers family. Interviewed afterward, he spoke of the bond between soldiers, and for him, color never entered into the equation. “You have to understand. In battle, you fight for each other.”

John Fox was accepted into Ohio State University, but he decided to transfer out to Wilberforce University because it was one of only three historically Black colleges in the country that offered ROTC training, and Fox was set on a career in the military. Upon graduation in 1941, Fox joined the newly activated all-Black 366th Infantry Regiment and became commander of his company. The 366th embarked for the Italian theater in late March 1944, becoming part of the 92nd division. With a forward post in Tuscany needing to be manned over the Christmas holiday, Fox volunteered for the extended four-day posting. It was a lonely assignment on the top floor of a 46-foot medieval stone church bell tower and his final assignment of the war. The day after Christmas, German mortar struck the bell tower just 50 feet from Fox’s location. A heavy German artillery barrage followed immediately after this first strike. Fox ordered the two men with him to retreat down the tower while he stayed and made a life-changing decision. He communicated over the phone to give coordinates of the town and instructed his men to fire high explosives, followed by a smoke round, so any of them remaining in the town could escape. Later, Fox gave his own position, but his men refused to fire on him. Instead, they transferred the call to have Fox’s shocking request approved by a general. Approval was granted within minutes, but before Fox’s coordinates were entered, Fox was asked one last time if he was sure about his request. Fox yelled in the phone, “Yes, damn it! There are more of them than there are of us. Give ‘em hell.” The shell was fired, and Fox was killed.

Child started his career in television in Boston before moving to New York as a freelance technical director. He began producing independent projects, including the film, “Gettysburg, The Boys in Blue and Gray,” and won over 26 writing and directing awards. He collaborated with figures such as Hal Holbrook, Walter Cronkite, and Andy Rooney. He was awarded honorary crew membership aboard the USS Franklin for directing and co-writing the film, “USS Franklin: Honor Restored.” His book, “Immortal Valor: The Black Medal of Honor Winners of World War II,” may be purchased on Amazon.com.