Inspired by a line in J.D. Salinger’s “The Catcher in the Rye,” a novel assigned to Anthony and his fellow rats by legendary VMI English professor Col. Herbert N. Dillard, Class of 1934, Anthony chose that ancient land. Little did he then know, but in so doing, he would find his life’s passion. “With the advance notice being less than a week to depart for Cairo, I had next to zero time to prepare,” Anthony recalled. “As a result, upon my arrival in Egypt, my culture shock was immediate, massive, embarrassing, and humiliating. But once this passed … I was smitten.”

After his stay in Egypt, a sojourn to the Gaza Strip and a firsthand introduction to the trauma and tragedy of the Palestine problem followed. Next, Anthony visited Greece and Jordan. Soon after, the Center for World Learning selected Anthony to lead a student group to Iran. There, in 1964, he lived with an Iranian family, the father of which had been the country’s foreign minister at the time of the 1917 Bolshevik revolution in Russia and, therefore, had known such 20th-century revolutionaries as Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky, and Josef Stalin. “This man was larger than life,” said Anthony. “He ‘adopted’ me, unofficially but in practically every other way, as his American son.”

Thanks to these transformative experiences, the young man who once thought he’d play baseball for a living had found a passion, purpose, and calling. Returning to the United States, he was granted one of three University Scholar Awards at Georgetown University, where he earned a Master of Science in Foreign Relations degree with distinction. Then, it was on to Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, where he earned a Doctor of Philosophy degree in international relations—and marked a first in university history by being appointed to the full-time faculty while still a student.

Anthony spent as much of the rest of the 1960s as he possibly could in the Middle East. In 1969, he was awarded a Fulbright, which ultimately took him to the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen, then the only Marxist-Leninist government in Arab and Islamic history. To this date, he remains the only American to have lived and conducted political research in that nation on a Fulbright.

Thanks to his extensive experience in the Middle East, Anthony simultaneously took on two other roles: Chairman of the U.S. Department of State’s educational and training program for American diplomats and other Foreign Service personnel assigned to the Arab region and deputy editor of the Middle East Journal, then the world’s most prominent scholarly periodical in English. During that time, Anthony completed his doctoral dissertation and finished his first book, “Arab States of the Lower Gulf: People, Politics, Petroleum.”

At the time, a career in the State Department seemed to be Anthony’s for the asking—indeed, he was offered the position of full-time chair of the diplomatic education and training program for mid-level Foreign Service personnel posted to the Arab region. Tempted though he was, curiosity moved Anthony to seek an answer to a probing question, one that confronts all applicants to prospective government positions tasked with dealing with sensitive matters pertaining to official rules and regulations.

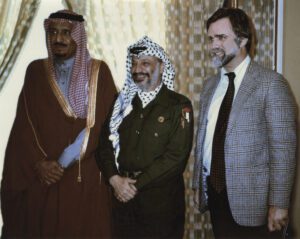

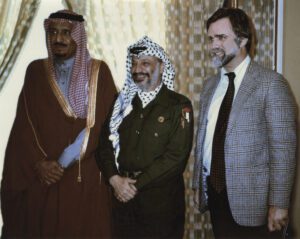

Pictured in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, Feb. 14, 1987, are (from left) Salman Bin ‘Abdalaziz Al Sa’ud, king of Saudi Arabia; Yasser Arafat, president of the Palestine Liberation Organization; and Anthony.

In explaining U.S. government policies, Anthony asked, would he always be allowed to tell the truth, or rather, would he be compelled to espouse whatever the official policy was, regardless of whether he thought it to be right or wrong? Informed there would be times when he would have no choice but to assume the latter approach, Anthony declined the position.

“I have a conscience, and I like to sleep at night,” he commented. “With my parents as role models, with VMI’s Honor Code engraved in my psyche, and in response to the silent voice that exists in most, if not all of us, whispering to me as I weighed these matters in my mind, I could not accept the offer.”

Anthony’s involvement with the State Department, though, didn’t end with that incident—far from it. Working as a government contractor, Anthony was called back into part-time service following the onset of the Iranian Revolution in 1979 to revise the Department’s curricula for training its diplomats, desk officers, intelligence analysts, and others assigned to monitor and project as well as protect America’s needs, concerns, and interests pertaining to the region.

In addition, he served as one of the Departments of Defense’s and State’s most sought-after specialists on Arabia and the Gulf for most of the next 40 years. In the process, each of these two government agencies would present him with one of three distinguished lecturer awards in their respective histories.

By this time, in the 1970s, the Middle East had shifted from the shadows to the forefront of American consciousness, thanks in part to the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, the ensuing oil embargo, and the consequent sharp rise in gas prices. With these factors in play, Anthony became in high demand as a speaker, offering his analysis of events in the region to corporate and military audiences—multiple times to the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School, the Joint Military Intelligence College, and the Defense Institute for Security Assistance Management—and higher education institutions at home and abroad.

Spurred by a desire to educate Americans about this critically important region, Anthony formed the National Council in 1983. In so doing, he did not forget VMI, as he worked with the late Col. James “Jim” Hentz, Ph.D.; Col. Patrick “Pat” Mayerchak, Ph.D.; Col. Wayne Thompson, Ph.D.; and other faculty he had taken to the Arab region on study visits to create the Institute’s first course on the Middle East.

In addition, Anthony played a pivotal role in enabling cadets to study Arabic abroad in Fes, Morocco—VMI’s summer program in that nation was begun by the National Council before being transferred to the Institute. At the National Council, one productive and fruitful year followed another, and before Anthony knew it, four decades had elapsed. Along the way, innumerable opportunities were afforded to cadets as interns and in the Council’s Leadership Development/Model Arab League program, and numerous VMI faculty members were able to take study visits to the region.

Anthony’s passion for his calling kept him going long past the time when many of his contemporaries had retired. When asked what his motivation was, he would reply, “I do what I love, and I love what I do.” Last year, health challenges prompted Anthony to slow down. Even so, there has been no diminution of his keen interest in the Arab region, the Middle East, and the Islamic world—or his support of VMI.

“The VMI experience,” he noted, “shows what can be accomplished, [and] not necessarily because of who you are or where you are from.” No matter where in the world he was—Cairo, Damascus, Bahrain, Baghdad, Doha, Kuwait, Muscat, Rabat, Riyadh, or even at home in McLean, Virginia—VMI was “never far from the center,” Anthony noted.

“In sum, there is no question that VMI is, and has always been, a unique, one-of-a-kind institution,” he continued. “Its business … is the cause of building leaders with character, of steeling one’s inner strength in the face of adversity, and of incorporating and developing a degree of self-confidence born not of ego or conceit but, rather, of hard-earned and self-effacing accomplishment. “For me and for countless others, there is no question that what Jackson is alleged to have said is true: ‘You may be whatever you resolve to be.’”