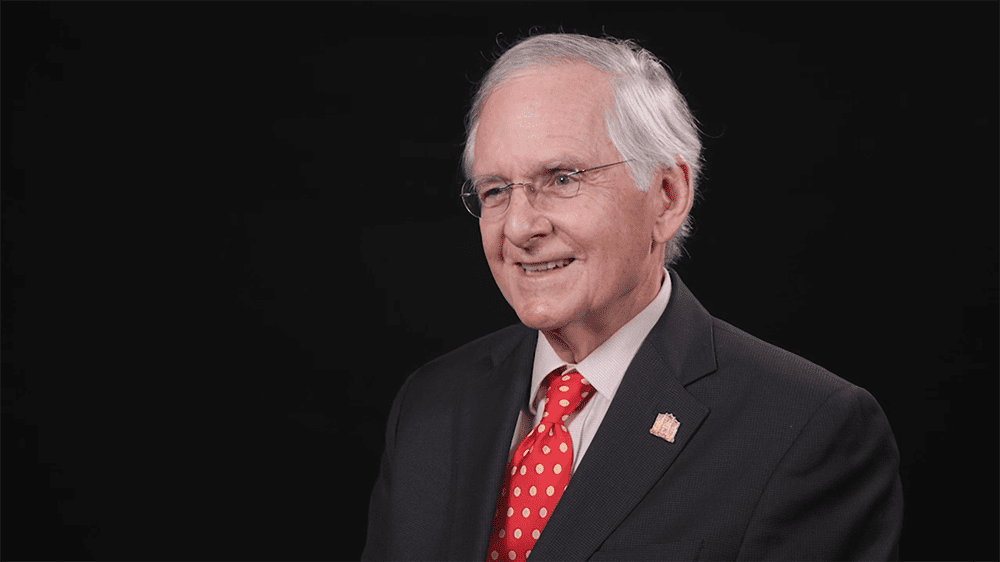

“I get jealous when my grandkids come home and show me their textbooks. I want to steal [the books] from them,” Richard Andrassy ’68, M.D., said.

Andrassy’s not a lawbreaker or an odd, textbook-pilfering guy. What he is, though, is curious – he’s a life-long learner.

Andrassy has been curious since elementary school, when he decided to become a doctor. He had an appendectomy in 10th grade and was fascinated. His fascination with medical studies increased when he saw a friend’s brother – a medical student – immersed in his studies.

“He was sitting at a desk in the dark with a lamp, with a huge medical textbook and studying and reading – I thought that was the coolest thing,” Andrassy recalled. Back at his own house, he “built a little desk, put it underneath my window and got a little lamp … and started studying and reading all the time.”

Andrassy was also interested in military service – his father was a former Marine who served in World War II. He had an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy but turned it down when he learned engineering – not pre-med – would be his mandated major.

He visited VMI and “liked the atmosphere.” The superintendent at the time, Gen. George R.E. Shell ’931, was a Marine – like his father. The Institute was small enough that Andrassy could play sports; he played baseball and ran track. As for pre-med studies, “there was a guy down there named Doc Carroll … who had a great reputation for getting people into medical school.”

After VMI, Andrassy earned his second degree from the Medical College of Virginia and then went on to serve in the Air Force. Since his graduation from MCV in 1972, he’s been working with students. He has always been at academic centers and says that is a good thing. Working with students keeps Andrassy up to date in his field.

“Most of the surgery I do today is different from we did when I was training in the ’70s. I had to keep learning and going back as a student myself,” Andrassy said. “You can get behind if you’re not reading and working with different people.”

Through his career, Andrassy had to learn to utilize imaging technology – like CT scans and ultrasounds. He has learned to perform surgery in an entirely different manner; most surgery is now minimally invasive and involves cameras and small incisions. Cancer treatment is different, too, and patients have a much better survival rate.

About 35 years ago, Andrassy moved to a new job in Houston, Texas. A big draw of the McGovern Medical School at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston was its sheer size. The university system teaches all kinds of health professions – nursing, medical, public health, dentistry and more – and includes one of the country’s largest trauma centers and a premiere cancer center.

For a guy who likes to learn, there was no better place. He is in the middle of health care innovations and new techniques, surrounded by fellow professionals in every specialty and field imaginable.

This was never truer than spring 2020, when COVID-19 changed the way the world does, well, everything. Initially, medical students were kept out of the hospital. “We didn’t want them to get infected and take it home to their families,” Andrassy explained.

The staff pivoted quickly, responding to the pandemic while continuing to teach. They learned to identify their own symptoms and are still tested at least weekly. Some doctors and nurses opted to sleep in hotels near the campus to avoid bringing the virus home. Technology allowed teaching to continue via video meetings. Even now, students are sometimes outside the patient’s room, watching and learning on computers or tablets.

“It really hit hard when you started seeing the number of people dying,” Andrassy said. After the escalation throughout the spring, August ended on positive note. The number of COVID-19 cases are lower, as are the number of patients on ventilators. Treatments are better, too. “We learned a lot about what drugs actually work … So, it’s getting better,” he noted.

In June, Andrassy stepped into a new position: Executive dean, ad interim of the McGovern Medical School at UTHealth. He’ll fill the position while the university conducts a search for a new dean – a process that could take a couple of years.

A new position, with greatly increased responsibility in the middle of a pandemic, and at a time when many of his brother rats were retiring, or at least thinking about it.

Did he have any second thoughts?

An emphatic, “No,” is his response. “Sometimes you have to step up to the plate and do what’s right,” Andrassy said, comparing it to a military field promotion.

Had he earned an undergraduate degree from any other school, Andrassy would likely possess the same calm resolve – that’s his personality.

Four years in VMI’s historic barracks, however, equipped him with some additional skills – skills he still uses.

Ask any VMI graduate what the Institute taught and “time management” along with “organizational skills” will be a quick answer. A busy doctor, Andrassy’s days can start with a 6 a.m. surgery and finish 16-plus hours later. Those skills are invaluable.

He also learned about leadership, how to treat others and how to be a good follower, to work well in the “chain of command” – which exists everywhere, though under slightly different names in civilian organizations. He’s seen many “bright young men and women get into trouble” because they don’t understand how to work within a chain of command.

Other schools often do a disservice to young students by not teaching “a strong base of right and wrong,” Andrassy said.

A steady donor to VMI over the years, Andrassy sees the value of what the Institute instills in young people. “I like the philosophy of VMI,” he said. “VMI still remains, overall, a very conservative school that is trying to teach good values.”